Since the seventies, forks have got stiffer. I don’t have any figures, but the diameters of stanchions and wheel spindles have increased. The stiffness of a tube goes as the cube of the diameter – that means if you increase a member from 25 mm to 50 mm diameter, the stiffness will increase by a factor of eight. The weight increase can be compensated by using thinner walled tube. Upside-down forks are hugely superior in this respect.

Decay time of oscillation for telescopic and leading link designs of fork. Roe and Thorpe 1979

Decay time of oscillation for telescopic and leading link designs of fork. Roe and Thorpe 1979

Everything else

You can experiment easily with tyre pressures, weight distribution, suspension and alignment, etc. and if you’re lucky it will make enough difference to reduce flutter. It’s a fact that heavier riders are better dampers than light ones. Trail (unless it’s adjustable) and lateral stiffness may be difficult to change, so you fit a steering damper.

Steering dampers

A lot of bikes come out of the factory with steering dampers already fitted by the manufacturer, so it’s not just fitting sidecars that causes the problem – it just makes it more obvious. The original solo item, if fitted by the factory is rarely effective with a chair and the very fact that the manufacturer had to fit one warns you to expect problems.

A given outfit may have forks with high lateral stiffness and still be stable with very little trail, while another similar outfit shakes its head like a wet dog. If it’s a classic bike, Ariel to Zündapp, you tighten up the factory-fitted steering damper! If it’s a Japanese machine from the 70s or 80s you have no such luxury, but it probably has so much trail that you can get away with it. It’s just heavy to steer.

Otherwise, you fit a steering damper and the unit of choice in the sidecar world is from the Volkswagen Beetle. (Ask yourself why VW couldn’t make inherently stable steering!) They are cheap and effective.

You can experiment easily with tyre pressures, weight distribution, suspension and alignment, etc. and if you’re lucky it will make enough difference to reduce flutter. It’s a fact that heavier riders are better dampers than light ones. Trail (unless it’s adjustable) and lateral stiffness may be difficult to change, so you fit a steering damper.

Steering dampers

A lot of bikes come out of the factory with steering dampers already fitted by the manufacturer, so it’s not just fitting sidecars that causes the problem – it just makes it more obvious. The original solo item, if fitted by the factory is rarely effective with a chair and the very fact that the manufacturer had to fit one warns you to expect problems.

A given outfit may have forks with high lateral stiffness and still be stable with very little trail, while another similar outfit shakes its head like a wet dog. If it’s a classic bike, Ariel to Zündapp, you tighten up the factory-fitted steering damper! If it’s a Japanese machine from the 70s or 80s you have no such luxury, but it probably has so much trail that you can get away with it. It’s just heavy to steer.

Otherwise, you fit a steering damper and the unit of choice in the sidecar world is from the Volkswagen Beetle. (Ask yourself why VW couldn’t make inherently stable steering!) They are cheap and effective.

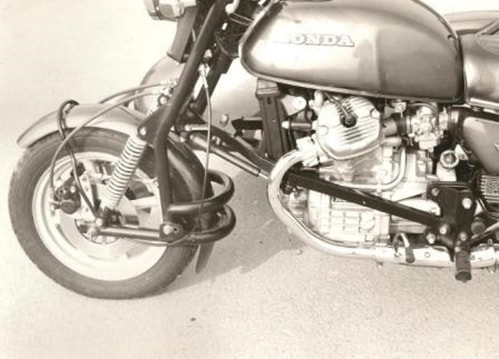

Wasp leading link forks. No steering damper visible.

Types of damper

The rider is a significant damper. That’s why the bars often don’t wobble until you let go. Heavy riders are better dampers than light ones.

Most modern dampers are hydraulic, although there are some cheap ones that are cylindrical, but rely on friction on the rod. Most classic dampers are of the friction plate variety. These have the advantage of being neat and adjustable. The damping rate is constant lock-to-lock, except for the stiction in the middle, which is handy, because that’s just where you want it and it drops off as soon as you move it.

The rider is a significant damper. That’s why the bars often don’t wobble until you let go. Heavy riders are better dampers than light ones.

Most modern dampers are hydraulic, although there are some cheap ones that are cylindrical, but rely on friction on the rod. Most classic dampers are of the friction plate variety. These have the advantage of being neat and adjustable. The damping rate is constant lock-to-lock, except for the stiction in the middle, which is handy, because that’s just where you want it and it drops off as soon as you move it.

Friction damper (Jawa) Hydraulic damper (Volkswagen)

Fitting a damper

If your bike was made with a friction damper, you are in clover. If it has a hydraulic unit for a solo, throw it away and fit one from a VW.

It can be really tricky to find the right position for a telescopic hydraulic steering damper. It must allow full lock-to-lock movement before bottoming or topping out and it must not touch forks, fairings or fittings (other than at the mounting points, of course). It must be fitted to a part of the forks which does not go up and down. The damping rate may vary considerably throughout the stroke as the angle to the forks changes, but this doesn’t really matter so long as you have effective damping near the middle. The damper does not have to be horizontal: the one on my EML is nearly vertical. If it makes the steering too heavy, move the fork end closer to the steering axis. The rubber bush provided is usually fine for the fixed end and a 10 x 10 rod end (Rose joint) will be needed for the moving end.

If your bike was made with a friction damper, you are in clover. If it has a hydraulic unit for a solo, throw it away and fit one from a VW.

It can be really tricky to find the right position for a telescopic hydraulic steering damper. It must allow full lock-to-lock movement before bottoming or topping out and it must not touch forks, fairings or fittings (other than at the mounting points, of course). It must be fitted to a part of the forks which does not go up and down. The damping rate may vary considerably throughout the stroke as the angle to the forks changes, but this doesn’t really matter so long as you have effective damping near the middle. The damper does not have to be horizontal: the one on my EML is nearly vertical. If it makes the steering too heavy, move the fork end closer to the steering axis. The rubber bush provided is usually fine for the fixed end and a 10 x 10 rod end (Rose joint) will be needed for the moving end.

Correctly fitted damper Incorrectly fitted damper

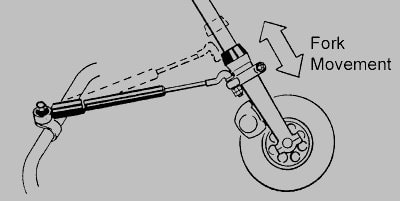

As the forks compress, the damper resists and deflects the forks to the left (in this case).

My own experience

My first outfit was a 1960 Triumph Thunderbird, Monza chair, 90 mm trail, lousy forks, standard friction damper. Shook its head violently at 25 mph unless the damper was screwed down. I still have the bike and I have now reduced the trail to 35 mm and it just shakes its head a bit at 10 mph. The same steering damper is just barely applied to make it sweet. The awful Triumph forks remain.

A 1978 Triumph Tiger with a Garrard GP followed. Much better forks with a trail value of about 115 mm. No steering damper was fitted or required, probably because of the high trail and stiffer forks.

My Yamaha XS 750 / Watsonian GP Sports had twistier forks and lots of trail. I lived with it until I fitted some BMW Earles forks with the necessary VW steering damper. It handled very well. Having a solid bottom yoke, the BMW forks were about as good as an Earles type can be and I never noticed any lack of stiffness.

I never used my Kawasaki 1100 with telescopic forks. A set of Unit forks went on straight away. I did have problems with lack of stiffness here and the front end would break away on hairpins. The Units were replaced with Wasp forks and the difference was enormous. The forks from Hedingham were undersized with sleeves inserted into the yokes to make up the difference. The Wasp forks were full diameter and just looking down at the front wheel, I could see everything was moving around much less. If I hammered it round hairpins now, the back end would eventually start drifting while the front tyre remained glued to the tarmac.

My trials, enduro and grasstrack outfits have all had leading links with steering dampers. The steering on all of them was very light with trail values under 10 mm. The steering damper wasn’t really to stop oscillation so much as to put some kind of resistance into the steering. I have an EML motocrosser housing an Africa Twin motor. One-piece frame, very little trail and doesn’t shake its head at any speed. A steering damper is fitted simply to stop it wandering on tarmac.

My sister had a Virago/Hedingham SS with Unit forks and it was just about the sweetest handling outfit I’ve ever ridden. The forks were of much larger diameter than on my Kwacker and thus stiffer. A couple of times it developed a shake and each time it was cured by replacing the pivot bearings. I think this is because the forks lose rigidity when the bearings are worn.

When the Virago was swapped for a Triumph Speedmaster, I nailed an EZS Rally to the Virago and that was (and still is) a pretty good handler too.

The last outfit I built with forks was the BMW K1200S with EZS Rally and the so-called EML-Solid forks. I was keen to do this because I wanted to know how Hossack-type forks would work with a chair. These forks are cost effective because you keep the original front suspension system (hence the “Solid” bit). The unsprung weight is enormous, but the BMW suspension coped with it perfectly. The original solo damper was left in situ, and I have no idea if it was needed. Trail was reduced to about 35 mm but the steering at low speeds was still very heavy, because with a wide tyre and a 60⁰ steering angle you are lifting the front of the outfit about 15 or 20 mm as you go from centre to full lock. Apart from that it worked very well indeed.

I converted the BMW to a Lefèvre hub-centre-steering system which is simply different from any kind of fork. It’s my second hub-centre-steered outfit, both without steering damper and never a hint of wobble or weave under any conditions. Why? Because of the extremely high lateral stiffness inherent in the design. Forks of any type are based on a three-foot lever mounted in bearings six inches apart! The corresponding lever with HCS only amounts to the radius of the wheel while the bearings are nearly half a metre apart. Do your own sums!

My first outfit was a 1960 Triumph Thunderbird, Monza chair, 90 mm trail, lousy forks, standard friction damper. Shook its head violently at 25 mph unless the damper was screwed down. I still have the bike and I have now reduced the trail to 35 mm and it just shakes its head a bit at 10 mph. The same steering damper is just barely applied to make it sweet. The awful Triumph forks remain.

A 1978 Triumph Tiger with a Garrard GP followed. Much better forks with a trail value of about 115 mm. No steering damper was fitted or required, probably because of the high trail and stiffer forks.

My Yamaha XS 750 / Watsonian GP Sports had twistier forks and lots of trail. I lived with it until I fitted some BMW Earles forks with the necessary VW steering damper. It handled very well. Having a solid bottom yoke, the BMW forks were about as good as an Earles type can be and I never noticed any lack of stiffness.

I never used my Kawasaki 1100 with telescopic forks. A set of Unit forks went on straight away. I did have problems with lack of stiffness here and the front end would break away on hairpins. The Units were replaced with Wasp forks and the difference was enormous. The forks from Hedingham were undersized with sleeves inserted into the yokes to make up the difference. The Wasp forks were full diameter and just looking down at the front wheel, I could see everything was moving around much less. If I hammered it round hairpins now, the back end would eventually start drifting while the front tyre remained glued to the tarmac.

My trials, enduro and grasstrack outfits have all had leading links with steering dampers. The steering on all of them was very light with trail values under 10 mm. The steering damper wasn’t really to stop oscillation so much as to put some kind of resistance into the steering. I have an EML motocrosser housing an Africa Twin motor. One-piece frame, very little trail and doesn’t shake its head at any speed. A steering damper is fitted simply to stop it wandering on tarmac.

My sister had a Virago/Hedingham SS with Unit forks and it was just about the sweetest handling outfit I’ve ever ridden. The forks were of much larger diameter than on my Kwacker and thus stiffer. A couple of times it developed a shake and each time it was cured by replacing the pivot bearings. I think this is because the forks lose rigidity when the bearings are worn.

When the Virago was swapped for a Triumph Speedmaster, I nailed an EZS Rally to the Virago and that was (and still is) a pretty good handler too.

The last outfit I built with forks was the BMW K1200S with EZS Rally and the so-called EML-Solid forks. I was keen to do this because I wanted to know how Hossack-type forks would work with a chair. These forks are cost effective because you keep the original front suspension system (hence the “Solid” bit). The unsprung weight is enormous, but the BMW suspension coped with it perfectly. The original solo damper was left in situ, and I have no idea if it was needed. Trail was reduced to about 35 mm but the steering at low speeds was still very heavy, because with a wide tyre and a 60⁰ steering angle you are lifting the front of the outfit about 15 or 20 mm as you go from centre to full lock. Apart from that it worked very well indeed.

I converted the BMW to a Lefèvre hub-centre-steering system which is simply different from any kind of fork. It’s my second hub-centre-steered outfit, both without steering damper and never a hint of wobble or weave under any conditions. Why? Because of the extremely high lateral stiffness inherent in the design. Forks of any type are based on a three-foot lever mounted in bearings six inches apart! The corresponding lever with HCS only amounts to the radius of the wheel while the bearings are nearly half a metre apart. Do your own sums!

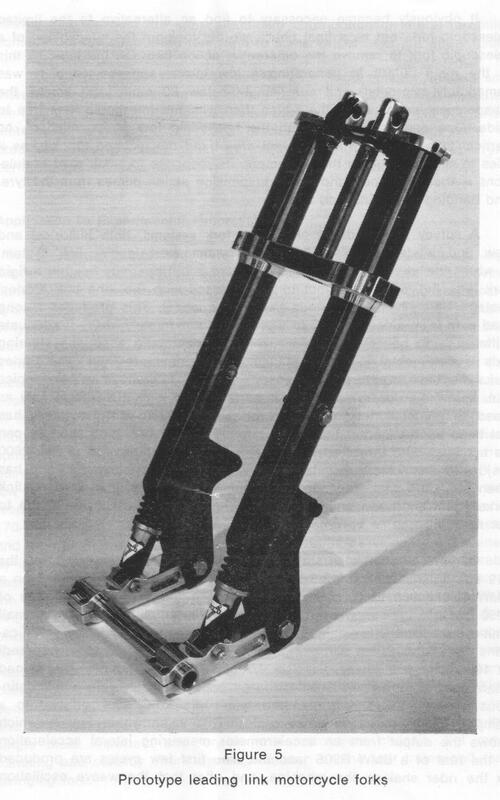

Thoughts on fork design for sidecar combinations

The only real contender is the leading link and I have a huge respect for the Wasp design. Choose large diameter tube and don’t sleeve down the yokes to accommodate a smaller tube. I am always disappointed when I see small wheel spindles used in links because the manufacturer wants to standardise the wheel and bearings. An integral bottom yoke is stiffer than a clamped one and a third yoke below the standard bottom one is really effective. (Lefèvre did this in 1980 and claimed it needed no steering damper.) Make sure the pivot bearings are large enough and in good condition. If all these points are ignored, the resulting forks are unlikely to be as stiff as the originals.

The only real contender is the leading link and I have a huge respect for the Wasp design. Choose large diameter tube and don’t sleeve down the yokes to accommodate a smaller tube. I am always disappointed when I see small wheel spindles used in links because the manufacturer wants to standardise the wheel and bearings. An integral bottom yoke is stiffer than a clamped one and a third yoke below the standard bottom one is really effective. (Lefèvre did this in 1980 and claimed it needed no steering damper.) Make sure the pivot bearings are large enough and in good condition. If all these points are ignored, the resulting forks are unlikely to be as stiff as the originals.

Lefèvre CX500/Squire ST2 (still with steering damper)

References:

Roe G E, Thorpe TE, Motorcycle Stability and Front Fork Design in The Manchester Engineer 123 No. 4

Foale T, Willoughby V, Motorcycle Chassis Design Osprey, 1984

Bradley J, The Racing Motorcycle, Vol 1 Broadland Leisure Publications, 1996

Roe G E, Thorpe TE, Motorcycle Stability and Front Fork Design in The Manchester Engineer 123 No. 4

Foale T, Willoughby V, Motorcycle Chassis Design Osprey, 1984

Bradley J, The Racing Motorcycle, Vol 1 Broadland Leisure Publications, 1996